Albert Oehlen: Home and Garden reviewed in The New York Times

June 11, 2015

NEW YORK – Albert Oehlen’s solo exhibition at the New Museum was recently reviewed by Roberta Smith of the New York Times.

Review: Albert Oehlen, a Master of Disciplined Excess

By Roberta Smith

JUNE 11, 2015

The German artist Albert Oehlen has been painting up a storm for more than 30 years, producing canvases that promulgate one kind of cross-fertilized chaos or another. The usual components include angst-free Abstract Expressionist brushwork, bits of popular advertising imagery, Surrealist automatist scribbles, spray-can vapor trails reminiscent of graffiti art and, at times, composite images built on the computer.

Born in 1954, Mr. Oehlen, one of the best artists of Germany’s postwar period, is known for his supposedly ironic and insincere approach to painting, but in recent years, especially, his work has conveyed a sublime sense of abandon and freedom — which he has identified as “my subject matter.”

Until now, his efforts have mostly been seen in New York in solo shows at commercial galleries. A museum show has been long overdue, and the New Museum has met the need with the small but terrific “Albert Oehlen: Home and Garden.”

This group of 26 paintings from 1983 to 2011 can’t possibly do Mr. Oehlen’s achievement full justice. But — thanks to Massimiliano Gioni, the museum’s artistic director and the show’s organizer, assisted by Gary Carrion-Murayari and Natalie Bell, its curator and assistant curator — the selected works on two adjoining floors create a compelling sense of his varied pursuit of turbulence, his expanding techniques and his deepening as an artist.

Like his close friend and comrade in irony Martin Kippenberger (1953-1997), Mr. Oehlen belongs to the second wave of German artists that washed over a largely unsuspecting New York art world in the mid-1980s. The first wave, which arrived mostly during the 1970s, included the painters Sigmar Polke, with whom Mr. Oehlen studied in Hamburg from 1978 to 1980, and Jörg Immendorff, whose circle he became part of in Düsseldorf while he was still a teenager.

Mr. Oehlen’s contemporaries tended to take a more adversarial, Dadaist approach, which he did not fully absorb. Picking and choosing — from Polke’s ravishment, Immendorff’s commitment to brush and oil paint — he has dedicated himself almost entirely to painting.

Even when he ventures into other mediums, painting rules: A rare installation piece included here features a real bed inhabited by an oil-on-canvas self-portrait, with a fake hand wielding a paintbrush.

It makes sense that Mr. Gioni emphasizes the word “excess” in the catalog. Mr. Oehlen’s paintings are overfull of the act of painting: of successive formal decisions; of different colors applied with brushes of various widths at different speeds; of digital images found or invented, manipulated and combined, and printed by sundry means.

His painting process represents uninhibited freedom in a way that is rare today because it is both extreme and self-contained, kept within the bounds of painting, which may be the perfect place for it. At the moment, of course, we are wearyingly familiar with acts of extremism in real space: immense galleries, looming fabricated objects and, by implication, lots of money. (Consider, for example, the Gagosian Gallery’s exhibition of huge aluminum sculptures by the earth artist Michael Heizer, whose art is more at home on the range.) In contrast, Mr. Oehlen overwhelms us with illusion, a weightless sturm und drang, signifying, it seems, nothing — until we look further.

The New Museum tracks the development of this pictorial excess. The third floor offers a kind of smorgasbord of styles that moves up and back in time. In one corner, two early self-portraits in shades of white, black and orange reflect attention to Picasso and the German Expressionists. Along the back wall is a fivesome of the more abstract kind of paintings Mr. Oehlen took up in 1988: soupy brown-gray blurs reminiscent of de Kooning, and embellished with sharper, brighter forms, as if the brooding artist had suddenly cheered up in the work’s final stages.

In one, white lines branch over the maelstrom, fastened down with curls of red, like electrical conduit. In another, a series of modernist rectangles in gray and yellow spans the canvas, like empty frames. In all of the works, long lines and bands begin to curve, and almost spiral, through the undergrowth.

These lines triumph and run playfully amok in works on the adjacent wall. They might almost have been made by another artist but are, in fact, contemporary with their neighbors. Mr. Oehlen composed them using a computer, fashioning scraps of digital patterns and looping lines. These he then enlarged and printed on canvas, or on paper that was sometimes pasted on canvas.

But an appealing handmade quality also emerges, as you start to see that there are painted lines extending, connecting to, or snaking among the printed ones. The results are jazzed, allover compositions that resemble Jackson Pollock’s dripped lines, pared down and forced through a screen of Op Art.

The digital paintings may or may not be the first ever made using a computer, but they may well be the first great ones. Denuded of color and shape, they may also be Mr. Oehlen’s first completely alive paintings. (Although another equally powerful line of endeavor developed at the same time, in 1992-93: the riotously bright paintings on awning canvas, printed with stripes or flowers, which were first shown as a group only last winter at the Skarstedt Gallery on the Upper East Side.)

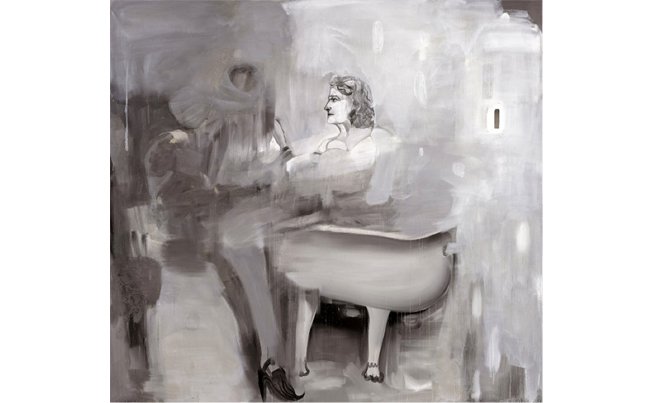

Mr. Oehlen, however, is not a slave to progress. The third floor also includes two later, more conventionally Expressionist paintings, notably “Bad” (or “Bath”) from 2003, a dour work with a woman in a bathtub emerging from, or sinking into, a luscious grisaille surface.

And in two works completed in 2011, Mr. Oehlen may even push Expressionism to new extremes: The brushwork obscuring parts of collaged advertisements can seem anguished, even tortured, like stretched skin. But it is the stunning digital works that form the hinge of Mr. Oehlen’s career, or at least this show. They open him to new techniques and a world beyond painting, while their lightness, refinement and linear energy foreshadow the works upstairs, in the show’s second half.

Here, the exhibition explodes with motion and color, beginning with manipulated images from the Internet and elsewhere, printed on canvas. The images are initially legible: “Captain Jack” (a huge red grinning inflatable head) and “Saints and Fighters” (a video game figure), both from 1997. Brushwork is so discreet that it almost seems camouflaged. In five paintings from 2001, the relationship is reversed, and the printed images are reduced to ghosts in immense pictorial machines — obliterated in clouds and looping lines of paint. Sometimes a carefully rendered shape hovers amid the madness: the tiny pink sphere at the center of “Born to Be Late,” or the grisaille nose-like shape in “Party Dreams.”

Of course, the real ghosts in these ethereal works are Mr. Oehlen’s predecessors — Polke, de Kooning, Pollock, Cy Twombly — whose vocabularies rise to the surfaces of his mash-ups in bits and pieces, only to sink again. But if the parts can look familiar, the whole feels like something hard-won and new.

“Albert Oehlen: Home and Garden” runs through Sept. 13 at the New Museum, 235 Bowery, at Prince Street, Lower East Side; 212-219-1222, newmuseum.org.

For more information on the exhibition click here.